Google’s search interface is so simple and reliable that most people prefer a quick Google search over their own local navigation tools. Frequently, when visiting clients I might say “Go to the Art Museum’s site” and rather than navigating to it from Bowdoin’s site they simply type into the browser’s address bar something like museum of art. More often than not, Bowdoin’s art museum appears as the first result in their search. Actually, even if they just search for museum Google often leads with the BCMA.

Before Google even gets into processing your search query, it first tries to understand what it can about you.

Traditionally, you wouldn’t expect to get such precise information by querying such an extensive data source without first providing all sorts of qualifiers. For example, let’s look at the National Register of Historic Places Digital Archive. Do a basic search for museum and you will get just what you asked for (and no more): a looooong listing of museums across the country that are on the national register. That’s not a knock against the NRHP. Like most large databases, its search interface is designed to return impartial, un-doctored resultsets when queried. If you take the trouble to tell it to restrict searches to Maine, it will oblige

you, but it won’t do it on its own.

Google is different.

Before Google even gets into processing your search query, it first tries to understand what it can about you. It considers things like your past history (both searching Google and online behaviors), native language, location, and what kind of device you are using. Google references this data to try to guess a user’s intent.

Let’s return to the Bowdoin Art Museum example. Google knows through your past search and browsing activity that you have a weighted interest in Bowdoin. In fact, if you start to type in museum, Google will start offering you auto-completions based on your past activity. It also knows your general location and can thus zero in on museums that may be of most interest to you. On the laptop I am using now, google takes my simple museum of art query and offers Bowdoin College Museum of Art as the first entry. Here is the rundown of the first six results I get at this time:

- Bowdoin College Museum of Art

- Current Exhibitions – Bowdoin College Museum of Art

- Portland Museum of Art: Home

- Home | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Bowdoin College Museum of Art (Brunswick, ME): Top Tips (TripAdvisor)

- Maine Art Museum Trail

I say at this time, because many things could happen that could change these results (in no particular order of importance):

- Portland Museum of Art could get national coverage, causing Google to bump its profile

- I might start doing a lot of interacting with Bowdoin’s Arctic Museum, causing Google to anticipate me preferring that museum in my searches

- I might get off a plane in Phoenix and make the same query, causing Google to reorient my results based on my new location.

Now, I actually know how to trick Google into thinking I am searching from Phoenix, Arizona. When I do here are the results I get when I query museum of art:

- Current Exhibitions – The University of Arizona Museum of Art

- University of Arizona Museum Of Art Archive of Visual Arts

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Tucson Museum of Art

- Home | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- High Museum of Art: Home

Entirely behind the scenes, Google has again slanted results to provide what it thinks I might want. Of course, it is doing a bunch of other things too that you might not consider:

- It is giving results in English (Google has data in over 100 languages)

- It is giving you localized results when possible

- It is filtering results by date

- It is promoting trending and/or relevant results

Many years ago one could state with some confidence that their site appeared “on the first page” of a Google search. Today too many factors go into serving up search results based on the searcher and not just the content searched to ever hope to make such a blanket statement.

All of this is to say that Google makes a lot of decisions about what results to return even before you enter a query. This allows Google to produce some extremely satisfying results, but it also makes it very difficult to determine what Google results will be. Many years ago one could state with some confidence that their site appeared “on the first page” of a Google search. Today too many factors go into serving up search results based on the searcher and not just the content searched to ever hope to make such a blanket statement.

You might have noticed that in the above searches the Metropolitan Museum of Art scored high whether searched from Brunswick, Maine or Phoenix, Arizona. Does the Met have the secret to mastering

Google? Well, hold on a second. We saw that the Met scores high for the query museum of art.. How does it do if I ask for art museum? Here are the results:

- Bowdoin College Museum of Art

- Current Exhibitions – Bowdoin College Museum of Art

- BCMA Visiting – Bowdoin College

- Collections (Bowdoin College Museum of Art)

- Portland Museum of Art: Home

- Maine Art Museum Trail

What a difference! To my mind museum of art and art museum are synonymous, but with just this slight change, the Met has fallen right off the board! In fact, the Met didn’t show up until the 10th screen of my query results! Clearly there is more to how Google returns results.

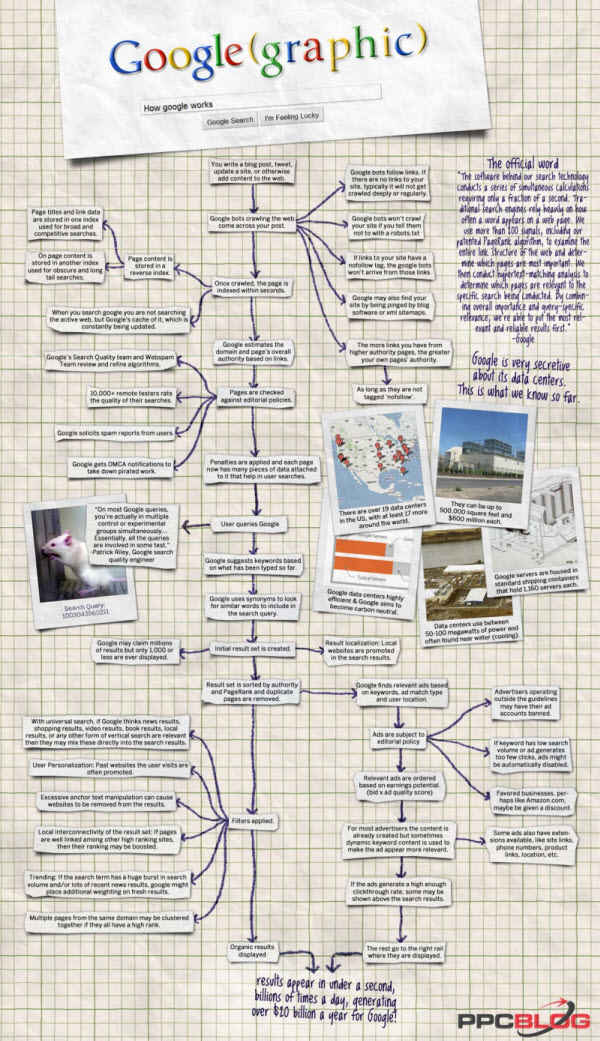

How Google Works Infographic by the PPCBlog

How Google Works Infographic by the PPCBlogTo understand that, we have to understand a bit more about how Google collects data. PPCBlog made a wonderful flowchart of the process Google uses to index content and how it searches content which I have included here for reference. Click on that image to get a better view of all the complexities going on in even the simplest of searches. Don’t worry if you don’t follow all the terminology or get lost trying to follow the diagram. The important thing to grasp here is that how a page appears is complicated.

In the early days of search engines, results were mostly weighted towards keyword usage. You may even remember the times when sites would simply repeat words over and over to raise their standing. If Bowdoin had ever stooped to such shenanigans, you might have seen a BCMA homepage with this text hidden in it:

<meta content="art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum art museum name="description" />

The page with the most usage of “art museum” would rocket right to the top of search results querying art museum. It was ridiculous, but it worked until the engines caught on and actually started punishing sites that did this (see: Pages are checked for editorial policies in the the infograph). Google has intentionally made it difficult for users to “juice the system” to improve their rankings and the result, overall, is a more organic, representative search tool. Trying to trick Google into raising your profile is in most cases a fool’s errand. There are still SEO “optimization” businesses out there that try to keep one step of

ahead of Google and purport to offer immediate results, but getting in business with one of these companies could actually end up penalizing your Google ranking in the long run. Learning to provide Google the data it wants and where it expects is the best way to boost rankings.

You might think your web page is important, but Google wants to know if it is relevant.

So what does Google want? More than anything else, it wants links! You might think your web page is important, but Google wants to know if it is relevant. Google determines relevancy largely by how often it is referred to by other sites. Do a search for college anywhere, and I bet US News’ College Ranking site comes up in the top 5. Why? Largely because every college, college-related business, and college-related news story links to them! They are deeply embedded in the Internet as a relevant college thing and Google’s search reflects that.

The second thing Google wants is to understand your vocabulary. Google analyzes page content to get a sense of how you describe yourself. For example, I am confident, having seen how the Met fared on my above searches, its pages frequently use the term “museum of art” and not so frequently “art museum.” To be “found” on Google, your page needs to provide clear words and terms that can be understood regardless of context. Here is a page I found by navigating around the Harpswell Historical Society’s website: https://sites.google.com/site/coneducationsite/. This page contains more than 200 links about various aspects of Harpswell, however it only ever mentions Harpswell by name six times and when it does it is in non-prominent places. The page linking this page tells us: “The purpose of this page is to provide a venue for the Harpswell Conservation Commission to develop resources to provide conservation education for the interested people of Harpswell as indicated by the Harpswell Open Space Plan.” But that context is entirely missing on the page itself. Without that stated context, Google will fail to bring this page to the attention of anyone looking for resources about Harpswell conservation.

Most of Bowdoin’s pages are designed to render well on multiple platforms. Some significant pages, deeply tied to design features, render poorly.

The last area I will cover about Google’s preferences relates to document structure and some other technical issues. Without going into too much detail, Google has certain expectations and shows preference to sites that are in alignment with these rules. The table below highlights some of these rules and also provides my assessment of how Bowdoin fares in applying these.

| Condition | Explanation | At Bowdoin |

|---|---|---|

| Use of title tag | HTML documents define a TITLE area that identifies the document’s main purpose | Typically good. Our CMS encourages users to make use of the title tag |

| Use of H1 and H2 tag | HTML documents define a H1 and H2 that work much like the TITLE tag and provide even more information. | Typically good. Our CMS encourages users to make use of the H1 and H2 tags |

| Site Map | Google allows sites to send them a site map that Google can use to assist them with indexing | Bowdoin provides a site map to Google |

| Robots file | Similar in nature to the site map, the robots file provides Google some ground rules for how we want them to index our site |

Bowdoin provides a robots.txt file to Google |

| Mobile awareness | Google gives extra attention to pages that render well on multiple platforms |

Most of Bowdoin’s pages are designed to render well on multiple platforms. Some significant pages, deeply tied to design features, render poorly. |

This article only scratches the surface of all the complexities involved with Google, but it has hopefully provided some insight into some of its inner-workings and maybe even answered a few questions you may have had. If you have questions about this article or how your Bowdoin site is doing on Google and what you can do to improve its ranking, reach out to us at Digital & Social Media.